.gif) FATHERS

FATHERS

„Dearest Father, You asked me recently why I maintain that I am afraid of you. As usual, I was unable to think of any answer to your question, partly for the very reason that I am afraid of you, and partly because an explanation of the grounds for this fear would mean going into far more details than I could even approximately keep in mind while talking. And if I now try to give you an answer in writing, it will still be very incomplete, because, even in writing, this fear and its consequences hamper me in relation to you and because the magnitude of the subject goes far beyond the scope of my memory and the power of my reasoning” – so begins Franz Kafka’s famous “Letter to his Father,” a monologue of the now-adult son, full of grudges and accusations against the tradition personified by the father.

The figure of the father is one of the oldest and most powerful cultural motifs, a theme that might seem to have been explored and explained in minutest detail. Nevertheless, it is continually taken up again, with the same passion and anxiety, now in fascination, now as a painful coming to terms. Our relationships with our FATHERS are still complex and mysterious, yet it is these relationships that mould our identity, our attitude to power and authority, and cause us to feel safe or excluded. Psychoanalysis pointed out the emotional ambivalence inherent in the son’s attitude to the father, which for Freud was expressed most dramatically in the Greek myth of King Oedipus. On the one hand, a little boy must love his father because he seems to him the wisest and best of all beings (indeed, even God is but an elevated image of the father), on the other, he sees the father as a disturber of his own instinctual life, so he wants to annihilate him and take his place. Freud believed it to be the cause of simultaneously affectionate and hostile impulses towards the father, which often persist throughout one’s life, unable to cancel each other out.

Later psychoanalytical studies by Melanie Klein and Jacques Lacan have offered a new interpretation of the Oedipal situation: the father is not only the hated and dangerous rival, but also the one whose presence questions the unlimited relationship between the mother and child. Michel Foucault elaborated on this theme in his essay on Hölderlin and the absence of the father: “Consequently, the father separates, that is, he is the one who protects when, in his proclamation of the Law, he links space, rules, and language within a single and major experience. At a stroke, he creates the distance along which will develop the scansion of presences and absences, the speech whose initial form is based on constraints, and finally, the relationship of the signifier to the signified which not only gives rise to the structure of language but also to the exclusion and symbolic transformation of repressed material.” Freud thus posits the father as a prototype in relation to which we first form our sense of self at an early stage of psychic life. All subsequent attempts at identifying or dissociating oneself to protect one’s individuality prove to be a mere variant or derivative of that original relationship.

Who, then, are our FATHERS? Who are WE in relation to our FATHERS? What do our biographies, family and generational histories tell about our mutual relations? How do we perceive fatherhood in social and political space, as well as the father’s presence or absence in religious and existential terms?

FATHERS direct us towards the past that we inherit. They are our link with history, as experienced by us directly – through our own biography. Heiner Müller, a German dramatist and director, claimed: “You can only write about history if you write your own historical situation into it.” Such history is a tangible, living entity; it is also a challenge that is sometimes difficult to meet. We always establish the relations between the past and the present with reference to our fathers, even if we have abandoned or are ashamed of them, or if we don’t even know who they were.

The artists invited to the Festival explore the motif of the father from various angles, on the border between what is personal and collective, private and public, examining how it shapes our national, cultural and religious identity, and, consequently, how it affects our sense of belonging, or of being orphaned or excluded. The context of Łódź is, of course, not without significance. The slogan of this year’s festival refers both to the past and the present of Łódź, an orphaned city at a time of cultural transformation. There is no other city in Poland with such a strong multicultural history and tradition, a city where the subject of fatherhood could emerge as equally important and inspiring.

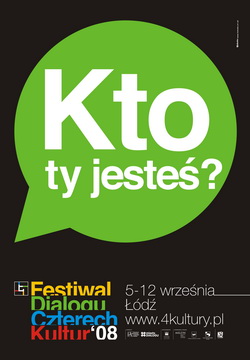

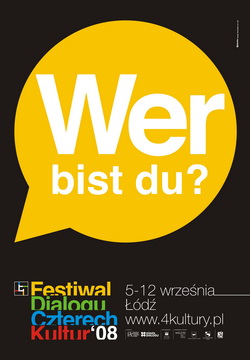

Plakaty festiwalu

.gif)